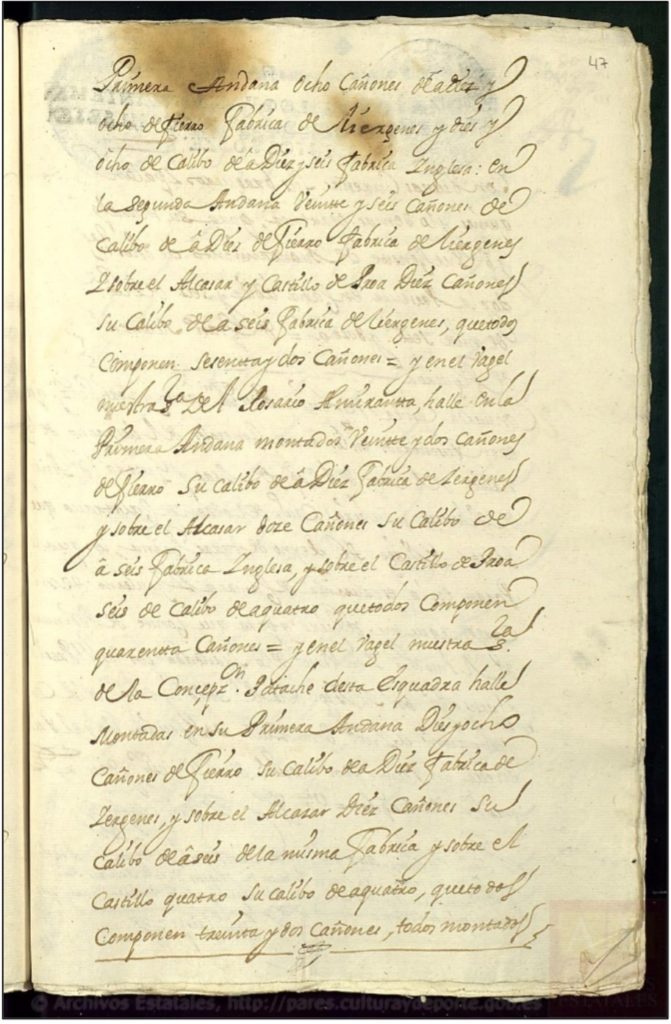

Since the discovery of several shipwrecks from the 1715 Fleet disaster in the Coast of Florida in the mid-1950’s and into the 1960’s, attempts have been made to match the names of ships, with the different shipwreck-sites. Today, over 60 years later, these early attributions have remained without scrutiny, being accepted by many as if they were fact. But how correct are they?

Let’s continue by looking at two of these ships: the Nuestra Señora del Carmen, San Antonio y San Miguel and the Nuestra Señora del Rosario y San Francisco Javier, the Capitana (Flagship) and Almiranta (rear guard ship) of the Tierra Firme Squadron of merchant vessels (Registros) under the command of Don Antonio de Echevers y Subiza, respectively. If you were to ask almost anyone today, which of these ships is located where, they would quickly tell you without hesitation that the remains of the Nuestra Señora del Carmen are in Rio Mar, while the remains of the Nuestra Señora del Rosario are in Sandy Point. For starters, I do not disagree that these are the ships in this general area. But the question is, what ship is at which site?

So, what led to these attributions? This comes from a letter written to the King of Spain at Palmar de Ays, in Florida, by Admiral Francisco de Salmon of the lost galleon Santo Cristo de San Román, Nuestra Señora del Rosario y Señor San José, Almiranta of the New Spain Fleet (Flota de Nueva España) of General Don Juan Esteban de Ubilla, on September 20, 1715. On this letter, when discussing the location of Echevers’ main two ships, in relationship to his own, Admiral Salmon says: “The Capitana of the Galleons of Echeverz and the Almiranta ran aground at five leagues distance, and all the other ships were sunk not far away; however, all the ships were sunk on the same island.”[AGI: Escribanía, 55C]Sandy Point and Rio Mar are located at less than three miles from each other. So basically, close enough to be within the same nautical league, when calculating a distance from a site to the north. With the knowledge that these wrecks represent two large 1715 fleet ships, just by the sheer number of cannons, this account would then support these ships being the ones associated with the wrecks in this area, which, as I have said, I do agree with. But can the finds and archival documents be used to finally provide a positive identification to each of these wrecks? Let’s see.

Taking a look at each ship, independently, we might be able to find differences that could help us locate something at each shipwreck-site that could provide a positive identification as to the ship located there.

The Nuestra Señora del Carmen started its life as the Hampton Court; a British Royal Navy 70-gun Third Rate ship-of-the-line (a man-of-war), launched at Deptford Dockyard in 1678. Rebuild in 1701, the Hampton Court was captured on May 2, 1707, off Brighton in the War of Spanish Succession by a French squadron under the command of Le Chevalier Claude de Forbin, continuing to serve in the French Navy (Marine Royale) as the 64-gun Le Hampton Court, until 1711, when it was sold at the port of Dunkirk to a French national by the name of Don Luis Robín. The Hampton Court was taken to the port of Cadiz by Don Luis Robín, who then sold it to Don Antonio de Echevers y Subiza on April 14, 1711, for the bargain price of 10,000 Pesos, being turned over to Don Antonio de Echevers y González, as his father’s representative. The Hampton Court was renamed Nuestra Señora del Carmen, San Antonio y San Miguel upon sale (the bill of sale shows the former name of this vessel as the “Lantoncur”, as an apparent poor phonetic attempt by the scribe, at spelling “Le Hampton Court,” with the French accent of its owner)[AGI: Contratación, 2716, No. 2]. At the time of its inspection in 1712, in preparation for its departure to Cartagena and Portobelo as the Capitana of the Tierra Firme Squadron of Master and Commander (Capitán de Mar y Guerra) Don Antonio de Echevers, its armament had been reduced to 62 cannons, as follows:

On its lower gun-deck there were 26 iron cannons: eight eighteen-pounders said to have been manufactured in Liérganes, Spain and the remaining 18, sixteen-pounders which were said to be of British manufacture. I must take a pause here to clarify that although both these types of cannons are nearly identical, there might have been an error in the document here, as the Spaniards were the ones known to use the sixteen-pounder, while the British used the eighteen-pounder (as per communication with Mr. Christopher R. Leverett, Historic Weapons Program Manager of Fort Matanzas & Castillo de San Marcos National Monuments, “a Spanish 16-pounder is often listed in English and American measurements as an 18-pounder.”) Continuing, the upper gun-deck, which included the main deck, also had 26 iron cannons, all ten-pounders manufactured in Liérganes, Spain, and as for the upper structures [the stern castle (alcazar) and forecastle (castillo de proa)], there were an additional 10 iron cannons, all six-pounders manufactured in Liérganes, Spain.

As for the Nuestra Señora del Rosario, it is documented that this was a ship previously named the Mars, built as a 52-cannon vessel, but which now had an armament of 40 cannons.[AGI: Contratación, 2716, No. 3] The Mars was said to have been a British captured vessel (presa inglesa), sold at public auction in the port of Dunkirk on August 17, 1711. Since it was said that this vessel was of British manufacture, then this must have been a British merchant ship or slave trader, renamed “Mars” at time of sale in 1711, or an assumption derived from it being in British hands at time of capture. In fact, the name “Mars” is a name more commonly found on vessels from France, the Netherlands and Sweden, but not from England. A search quickly revealed that only one ship had served in the Royal Navy with the name “Mars” prior to the time this vessel was captured in 1711. This was way back in 1665, when a Dutch VOC vessel by the name of Mars was captured in the Second Anglo-Dutch War, and integrated into the Royal Navy, where it retained its original name of Mars while serving in this navy, until being sold in 1667. Now, if this had been a previous British Royal Navy capture, built as a 52-cannon vessel, later renamed Mars, the only two candidates would be the Pendennis (captured by the French in 1705 and sold in 1706) and the Chester (captured in 1707, at which time it disappears from the records). But none of these two 50-cannon British Fourth Rate ships-of-the-line, with a burden of 681 tons and 663 tons, respectively, by British standards, match that of the Nuestra Señora del Rosario, at 312 tons, by Spanish standards, even after taking into consideration the reduction of cannons from 50 to 40.

Since there are no British Royal Navy ships with the name “Mars” in this era, British built or not, and it does not match the only two possible Royal Navy captured ships at the time, then we can say with certainty that this was not a vessel previously operated by the Royal Navy, but a British merchant ship or a slave trader which might have retained its original name when purchased by its current owner or renamed at the moment of sale in 1711. When sold at auction, this vessel was purchased by Don Angel de Messi Norman, Master and Commander (Capitán de Mar y Guerra) of the French Navy, who, because he did not speak Castilian, he later hired a businessman from Cadiz by the name of Don Pedro Ignacio de Sarmon, who was a Flemish national, to serve as interpreter for the sale of this vessel in Spain to Don Anotnio de Echevers y Subiza; a sale that took place on July 24, 1712 for 30,000 Pesos. At the time of the sale, the vessel was renamed Nuestra Señora del Rosario y San Francisco Javier. The same inspection conducted on the armament of the Nuestra Señora del Carmen was also done on the Nuestra Señora del Rosario, which had been slotted to be the Almirantaof the Tierra Firme Squadron of Echevers. This inspection revealed that its armament was composed of 40 cannons, as follows:

The lower gun-deck, which included the main deck, had 22 iron cannons, all ten-pounders manufactured in Liérganes, Spain. On the stern castle (alcazar) there were 12 iron cannons, all six-pounders of British manufacture and on the forecastle (castillo de proa) there were an additional six cannons, all four-pounders, no mention as to their place of manufacture.

So, in summary, the Nuestra Señora del Carmen had been a Royal Navy vessel (built and operated by the Royal Navy), whereas the Nuestra Señora del Rosario had not. As for the armament, the Nuestra Señora del Carmen had, between its eighteen and sixteen-pounders, 26 cannons of types not found on the Nuestra Señora del Rosario. The same occurrence can be found on the Nuestra Señora del Rosario, which had four-pounders (a total of six of them), which were not part of the cannon armament of the Nuestra Señora del Carmen. One can say that just the difference in the cannon types alone should have been enough to make this an easy task. Finding a cannon that did not belong on either site would have quickly revealed what ship was there. But soon enough a problem arose. No one seemed to have taken the time to take the bore measurements of the cannons in-situ on each site, or to properly document the cannonballs discovered, to be able to make use of this information. What started as an uplifting discovery quickly turned into a five-year search for answers that kept on eluding me at every turn. But that search finally came to an end this year, when 30-year 1715 Fleet salvor and historian, Mr. Thomas Gidus from Florida, shared with me several newspaper articles from 1955, which answered some of these questions.

The first of these articles, from the Fort Pierce News-Tribune dated June 22, 1955, mentioned that two cannons had been salvaged at Sandy Point by a “salvage trio”, led by Art McKee Jr. This article read as follows:

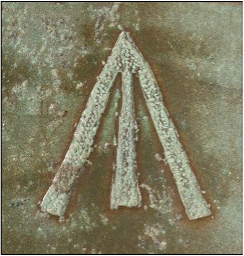

“A KEY TO age of a pair of coral-encrusted cannon retrieved from the ocean floor north of Fort Pierce Tuesday night is given salvage operators by this stamped brand on the barrel of one of the pieces hauled aboard. The emblem is a set of crossed anchors that has retained its sharpness remarkably well in spite of its estimated age. The leader of the salvage trio, Art McKee, Jr., an old hand at retrieving treasure from the seas, estimates this piece to be at least 300 years old, but final determination await appraisal by antique experts.”

As per the book The Art of the English Trade Gun in North America by Nathan E. Bender, page 21, “The King’s Broad Arrow mark has a particularly long history, used to denote the property of the English monarch. One of its earliest uses on a dated record is from 1330, the time of King Edward III. Use of the broad arrow mark was wide-spread in the Royal Navy.”

On June 24, 1955, the Miami Herald identified this “salvage trio” saying: “Roger King, 21, of Vero Beach several months ago found the wreckage 4,400 yards (there is a typo on the distance in here, having been correctly reported by this same newspaper on June 22, 1955, as being 400 yards) offshore about eight miles north of Fort Pierce. He and his partners, Art McKee Jr., museum operator in the keys, and Jack Carr, a Vero Beach telephone lineman, formed a salvage company to explore the wreckage.” Another report from the Orlando Sentinel from June 26, 1955, revealed these two last cannons salvaged to be “nine feet three inches overall with a five-inch bore”. As for the member of the salvage trio by last name “King,” I must add in here that his full name might have been John Roger King, as a later report from the Miami Herald, dated July 27, 1955, includes a statement by State of Florida Land Agent Sinclair Wells, which reads: “Jack Carr and John R. King of Vero Beach located the remains of the ship and later asked Arthur McKee Jr. of Tavernier to join the hunt.”

Although the initial report from June 24, 1955, from the Miami Herald, included that a “14-foot” anchor and 14 cannons had already been salvaged by this date, this was clearly in error when it came to the cannons. A more accurate report would be published on July 27, 1955 by this same newspaper (the Miami Herald), when reporting that “McKee said in a letter the group had recovered 13 ‘twelve-pounders’ from the wreck, several hand grenades, an anchor and cannon balls” and that “Four of the guns are definitely British…and bear the crossed anchor emblem of the Royal Navy”, and that “The anchor carries the broad arrow markings of the Royal Navy.” Two more cannons were said to still be on the ocean floor at the site, and that they would be salvaged as soon as weather conditions permitted. These two other cannons were also salvaged shortly after.

I must take a pause to mention that Robert Weller seems to have believed that this shipwreck-site had been known since World War II, as he mentioned in his and Ernie Richards’s book Shipwrecks Near Wabasso Beach, in the chapter titled “Sandy Point Wreck” (1715), that “Kip WagnerKip Wagner (1906 – 1972) was instrumental in the formation of the team that later became the Real Eight Company and one of the greatest salvage groups that ever explored the 1715 Fleet wrecks. He ... More mentioned that during W.W.II he helped Art raise eighteen cannons to sell for scrap and to put in his museum in Plantation Key”. This is more than likely an assumption by Weller, which will not be discussed further, as not only did Art McKee Jr. not contest Jack Carr and John R. King being given credit in the 1950’s for the discovery of this wreck, but also, as Mr. Gidus pointed out, the earliest newspaper mention of Kip WagnerKip Wagner (1906 – 1972) was instrumental in the formation of the team that later became the Real Eight Company and one of the greatest salvage groups that ever explored the 1715 Fleet wrecks. He ... More in Florida dated from the 1950’s, having become aware of the 1715 Fleet shipwreck-sites from Steadman Parker, and Kip WagnerKip Wagner (1906 – 1972) was instrumental in the formation of the team that later became the Real Eight Company and one of the greatest salvage groups that ever explored the 1715 Fleet wrecks. He ... More himself does not mention on his own book, any participation in the salvage of cannons from a 1715 Fleet wreck-site during World War II. Also, the mention of cannons being salvaged during World War II could very well be a reference to cannons being salvaged from another wreck during this war, such as the 1695 wreck of the Winchester, which remains were discovered in 1938 in Caryfort Reef South, off Key Largo, by a local fisherman who spotted a cannon, and from which cannons are known to have been salvaged during World War II, to be scrapped for their metal, to be used in the war effort.

The initial belief that the wreck at Sandy Point could also be a “sunken British ship”, and the similarity between these guns and those recently salvaged by Art McKee Jr. at Looe Reef in the Florida Keys from the 1744 wreck of the Looe, which largest guns were twelve-pounders, seems to have caused an error in thinking that all these cannons were also twelve-pounders. Taking into consideration the slight reduction in the bore size by the thick layer of corrosion covering the cannons when salvaged, the bore diameter of five-inches is a better match with the roughly 5.3 inches found on eighteen and sixteen-pounder of the time, than the 4.62 inches found on twelve-pounders. The identification of the Royal Navy marking on the same cannon said to have a bore diameter of five-inches would also be consistent with these being cannons of a larger caliber, as we already saw that the armament inspections of the Nuestra Señora del Carmen and the Nuestra Señora del Rosario revealed that both these ships only carried ten-pounders of Spanish manufacture, but no British twelve-pounders, and that British cannons of this larger caliber type (be these the sixteen or eighteen pounders) were only found on the Nuestra Señora del Carmen.

Having looked at the specifics about each vessel, with one being constructed as a Royal Navy ship, while the other serving as a merchant ship or slave trader, and the data on the armament, let’s now take a look at the documentary evidence and at the treasure finds.

A letter documented by researcher Jack Haskins, written by Don Antonio de Echevers on August 24, 1715, at the Salvage Camp (Real) of Nuestra Señora de la Popa, to Captain Manuel de Miralles, Deputy Commissioner for the Relief Effort of the Fleet (Comisario Diputado para el Socorro de la Flota) in Havana, describes the condition of his Capitana, the Nuestra Señora del Carmen, and his Almiranta, the Nuestra Señora del Rosario, at the time of sinking.

According to this letter, Echevers says: “I will send many of my people to St Augustine in a launch with what victuals we could recover, and they will depart tomorrow…although my Capitana stayed intact it fell over on the starboard side in such a way that we are unable to recover anything from it. My Almiranta broke up in three pieces because it hit upon some rocks…”

So, we can deduce from Echevers’ own statement that his Capitana had not been overtaken by the treacherous reefs, and that it had come to rest in a sandy area inside the reef, as, although the Nuestra Señora del Carmen was a very large and heavy vessel, weighing 713 tons (by Spanish standard of the time) with a draft of 17 feet, 3 inches, it had remained mainly intact, which is something that is not possible had the ship remained over the reef for a prolonged time during the hurricane.

Where 120 souls onboard Echevers’ Almiranta perished, the opposite can be said of his Capitana, where only 4 people drowned.

Robert Weller, who knew well the underwater terrain at Sandy Point, based on the physical evidence at the site, reconstructed how the ship that sank there, came to its tragic end. This narrative, for which Weller believed that the ship at Sandy Point was Echevers’ Almiranta, says that this ship “took aim at a point of land, first striking the reef about 3,000 feet offshore, where there lies a concentration of ballast stones -near a reef that rises to within sixteen feet of the surface. As it bounced over the flat anastasia rock bottom it dropped cannons, seemingly in a row. The last cannons were spilled about 700 feet from the beach, just before reaching a sandy drop-off twelve feet deep.”

The narrative is well prepared. But it does not match a ship that broke in three over the reef, at the mercy of the hurricane, with a great loss of life. But it does fit perfectly with what we know about the sinking of the Nuestra Señora del Carmen. In accordance with this narrative, the Nuestra Señora del Carmen would have hit the reef at 3,000 feet from shore. At this point, Weller documents cannons, “seemingly in a row”. This is consistent with a ship dropping cannons in an attempt to free itself from the reef to prevent it from being shredded to pieces by the jagged coral with the fury of the ocean. As, the cannons were dropped and the ship became lighter, it would have been released, being pushed further toward shore, where it would get stuck again, forcing more cannons to be dropped. The cannon trail seems to indicate that this continued for some 2,300 feet, until about 700 feet from shore, where, ultimately, the ship finally reached a “sandy-drop off twelve feet deep” where it grounded, falling over on its starboard side, as soon as the storm surge receded.

The narrative presented here would not be possible at Rio Mar, where, according to a Beach Dive Guide: “This is the best reef on the east coastline and is located only 50 feet from the beach. At low tide, it protrudes from the water and is visible from shore. This reef, unlike the others, is solid even in the shallow areas (15 feet or less) with many cracks, crevices, and ledges which extend for at least 200 yards.” There is no place here to park a large ship during a hurricane, without it being battered and destroyed by the constant pounding of the waves over the shallow reef, which is what ultimately happened to the Nuestra Señora del Rosario. The presence of such a reef here, “solid even in the shallow areas” also explains why there was such a great loss of life.

But this is not the only evidence that can be examined. There is one last piece of evidence, and that is the treasure finds themselves.

Since a shipwreck that remained mainly intact, laying on its starboard side, would have been an easy salvage, then very little treasure should have remained. This is consistent with the finds at Sandy Point over the years. Mel Fisher’s groups, Universal Salvage Company, Inc., under Kip Wagner’s Real Eight Co. lease, initially recovered in 1963, three gold coins along the trail and between 1,200-1,500 silver coins at the sandy bottom. But as Robert Weller tells us: “since that time surprisingly little salvage work has been accomplished on the site. Several salvagers have looked, and a few artifacts have been recovered…but nothing worthwhile.”

Now, with the complications of salvaging treasure that has spilled over a reef from a ship that has broken in a hurricane, we should then expect for there to be more finds of this type on such site, and again, this is what we find at Rio Mar.

As documented by Robert Weller, here is a list of finds at Rio Mar, which includes items that certainly should not be present from a ship that had remained intact:

“2 gold bars

1 gold quoit

22 gold nuggets

Several ounces of gold flakes

140 gold coins

617 silver coins

1 copper maravedi

1 English gold guinea

1 emeral teardrop

1 tree-carat ruby stone

1 gold finger ring with amethyst

8 gold rings

5 gold earrings

2 gold brooches

2 gold flower ornament holders

1 gold hat pin

1 gold hair piece

2 gold crucifixes

3 pairs of gold cuff-links

3 gold pendants

3 gold wire pieces

1 gold chain with pendant

1 gold grooming spoon

9 brass buttons

7 brass buckle

1 brass candle snuffer

1 clay pipe

1 die

1 silver candelabra

1 brass dish

3 silver spoons

3 silver forks

1 silver knife handle, pewter plates, cups, bowls, swords, daggers, a brass blunderbuss, and many other ship’s artifacts.”

In conclusion, all the evidence studied, from the cannons found at Sandy Point with a bore diameter consistent with sixteen/eighteen pounders, to the Royal Navy markings found on some of these cannons and on the anchor, added to the documentary evidence of the disaster in relationship to the conditions and location of the wrecks at Sandy Point and Rio Mar, and to the finds on each site, all point to only one answer, the Nuestra Señora del Carmen is the ship found at Sandy Point, while the Nuestra Señora del Rosario is at Rio Mar.

Bibliography

Archivo General de Indias (AGI):

Escribanía, 55C

Contratación, 1276, N. 2 and N. 3

Santo Domingo, 419

Bender, James, Dutch Warships in the Age of Sail, 1600-1714: Design, Construction, Careers and Fates. Barnsley, UK: Seaforth Publishing, 2014.

Bender, Nathan E. The Art of the English Trade Gun in North America. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Inc. 2018.

Cloyd, Allison M. Cannon Bore Measurements from Castillo, email from the Historic Weapons Program Manager at Fort Matanzas & Castillo de San Marcos National Monuments to the author, Jorge A. Proctor. March 21, 2022.

David Taylor. “The History of the Broadarrow and its Use in the Antipodes, Survey Review”, Vol. 43, Issue 323, 2011. pp. 493-504.

de Tousard, Louis. The American Arillerist’s Companion, or Elements of Artillery, Vol. I. Philadelphia, PA: C. and A. Conrad and Co. 1809.

Gidus, Thomas. Facebook message to the author, Jorge A. Proctor. March 27, 2022.

Haskins, Jack. The 1715 New Spain Flota and Tierra Firme Galleons History [Unpublished and undated research paper].

Leverett, Christopher R. Cannon Bore Measurements from Castillo, email from the Historic Weapons Program Manager at Fort Matanzas & Castillo de San Marcos National Monuments to the author, Jorge A. Proctor. March 21, 2022.

Weller, Robert and Richards, Ernie. Shipwrecks Near Wabasso Beach. West Palm Beach, FL: EN RADA Publications. 2010.

Weller, Robert. Sunken Treasure on Florida Reefs. West Palm Beach, FL: Treasure Brokers. 1996.

Singer, Steven D. Shipwrecks of Florida: A Comprehensive Listing. Sarasota, FL: Pineapple Press, Inc. 2011.

Three Decks Forum, British Fourth Rate ship ‘Chester’ (1691) at: https://threedecks.org/index.php?display_type=show_ship&id=146

Three Decks Forum, British Fifth Rate ship ‘Looe’ (1741) at: https://threedecks.org/index.php?display_type=show_ship&id=5164

Three Decks Forum, British Fourth Rate ship ‘Pendennis’ (1695) at: https://threedecks.org/index.php?display_type=show_ship&id=497

Winfield, Rif. British Warships in the Age of Sail, 1603-1714: Design, Construction, Careers and Fates. Vol. 1. Barnsley, UK:Seaforth Publishing. 2009.

Windfield, Rif and Roberts, Stephen S. French Warships in the Age of Sail 1626-1786: Design Construction, Careers and Fates. Barnsley, UK: Seaforth Publishing. 2017.

Beach Dive Guide. Treasure Coast Beach Diving Sites: Sebastian to St. Lucie Inlet, at: https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&cad=rja&uact=8&ved=2ahUKEwjPm_6Bstv2AhVRZzABHRFdBvcQFnoECAUQAQ&url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.deepsixintl.com%2FPDF%2FBeachDiveGuide.pdf&usg=AOvVaw0DfLexhbJrSDK2KP1MaSzf

Newspaper Articles:

“Seek New Cannon from Old”, The Herald (Miami, FL, Ed.), April 21, 1942, Page 12-A.

“A KEY TO age of a pair of coral-encrusted cannon…”, Fort Pierce News-Tribune (Fort Pierce, FL, Ed.), June 22, 1955, Page 10.

“Treasure Hunt: Octopus in Cannon Sneers at Skin-Divers”, The Miami Herald (Miami, FL, Ed.), June 22, 1955, Page 1-C.

“14 Cannon Pulled Up By Divers”, The Miami Herald (Miami, FL, Ed.), June 24, 1955, Page 1-C.

“ANCIENT CANNON”, The Orlando Sentinel (Orlando, FL, Ed.), June 26, 1955, Page 10-A.

“From Sunken British Ship: Florida Gets Treasure Cut”, The Miami Herald (Miami, FL, Ed.), July 27, 1955, Page 3-B.

Carola, Chris. “Project confirms NY fort’s old guns came from Florida wreck. Project confirms NY fort’s old guns came from Florida wreck” The San Diego Union-Tribune (online), March 24, 2016, at: https://www.sandiegouniontribune.com/sdut-project-confirms-ny-forts-old-guns-came-from-2016mar24-story.html