This article, by Phil Flemming and Ben Costello, was published in the January 2015 edition of The Numismatist, and the full text of the article is included below.

Three hundred years ago, a Spanish treasure fleet was lost in the waters off Florida’s eastern coast. Over the last five decades, salvage operations on known wreck sites have recovered significant quantities of Spanish Colonial coinage dating to the reigns of Carlos II (r. 1665-1700) and Philip V (r. 1700-46). Numismatically, little was known about these eras, which included the inauguration of gold coinage at Mexico City (1679) and Lima (1696). One of the first appraisals of the significance of the “1715 Plate Fleet”—so called because of its large silver cargo (plata being the Spanish word for silver)—is W. Frank Allen’s article entitled “Previously Unknown Spanish Gold Coins,” which appeared in the February 1967 issue of The Numismatist. The story is as relevant today as it was 47 years ago.

Loss of the Fleet

Thanks to contemporary reports and letters first uncovered in the mid-1960s by Dr. Nancy Farriss at Spain’s Archivo General de las Indias, much of the story of the 1715 Plate Fleet’s sinking is known. At sunrise on July 24, 1715, 12 ships weighed anchor and sailed confidently out of the harbor in Havana, Cuba. Six days later, the vessels found themselves in deep trouble. Carrying millions of pesos in gold and silver, the combined Mexican flotilla of Admiral Juan Esteban de Ubilla and the private merchant flotilla (not an official Tierra Firme fleet) of Antonio de Echeverz had tried that day to sail past an ominous storm bearing down from the Bahamas. The bulky, treasure-laden galleons and their smaller escorts quickly learned they could not outrun a hurricane. Almost 182 years before, 16 ships of Spain’s 1533 fleet had met the same fate in the same place.

By midnight, 100-mile-per-hour winds, heavy rain and massive waves broke over the fleet. The hurricane had trapped the ships in the narrow Old Bahama Channel and was driving them toward the reefs along the Florida coast. Before dawn on July 31, 11 of the 12 ships, including all the treasure galleons, were lost, some capsizing in deep water, some torn apart on Florida reefs, and a few driven ashore intact. Nearly a thousand crew and passengers, including Admiral Ubilla, perished in the hurricane’s fury. Come sunrise, the full extent of the disaster was revealed, with bodies, wreckage and dazed survivors littering the beach.

Castaways, Campsites & Salvage

The survivors’ first order of business was to construct makeshift camps. Food and drinkable water were precious commodities, as was protection from the Florida sun and hostile natives. When the Spanish Colonial authorities learned of the disaster, they responded quickly from Havana and St. Augustine, Florida, but in truth their efforts were directed more at salvaging the king’s treasure than rescuing survivors.

By September, the camps still held many castaways, but they also served as bases for salvage operations. Pirates and privateers responded to the disaster nearly as fast as the Spanish Colonial government. Jamaica’s British governor encouraged raids on the salvage camps, as did the governor of Virginia. For three years, the wreck was sporadically salvaged and plundered. By the end of 1718, survivors, salvors and pirates were long gone from Florida’s sandy shores. Three winters had obliterated most of the wreck sites, and the Spanish were content with having recovered what they believed was the majority of the treasure. However, a fortune in silver and gold still lay scattered along the Florida coast, where it would remain

untouched and forgotten for nearly 250 years.

Enter Kip Wagner

Modern efforts to find the remains of an “unknown” Spanish treasure fleet began in earnest in the late 1950s. Kip WagnerKip Wagner (1906 – 1972) was instrumental in the formation of the team that later became the Real Eight Company and one of the greatest salvage groups that ever explored the 1715 Fleet wrecks. He ... More, a retired contractor, was the unlikely catalyst. As he described in his 1966 memoir, Pieces of Eight, since the early ’50s he had heard rumors of gold and silver coins washing up on Florida beaches. Intent on finding the source of the coins, he teamed up with his friend Dr. Kip Kelso, an amateur Florida historian.

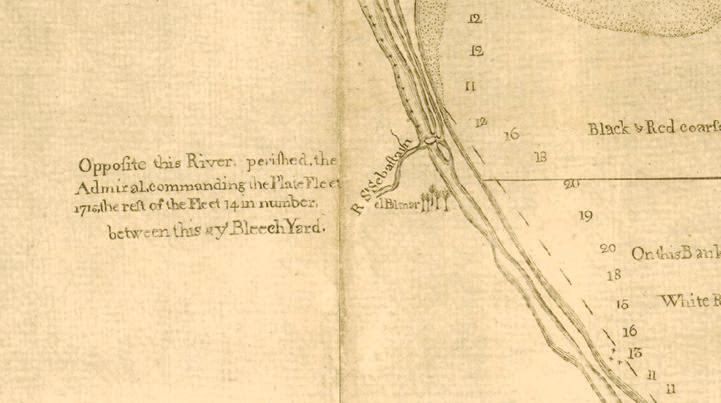

Together they began researching shipwrecks that might have occurred around the time of the coins’ production. In 1959 Kelso found an 18th-century map of Eastern Florida published by cartographer Bernard Romans. In 1754 Romans surveyed the area of the wrecked fleet and reported that “the masts of a Fleet [are] still visible above the water. …after a northeast wind, those of our crew who walked the beach repeatedly found pistareens and double pistareens.” On the map, next to what he called the Sebastian River, he noted, “Opposite this river perished the Admiral commanding the Plate Fleet of 1715.”

Though it is now unclear exactly where Romans saw the masts and whether they had anything to do with the 1715 wreck (very likely they did not), Wagner was convinced that Romans had accurately identified the site. He searched the area surrounding modern-day Sebastian Inlet (with a bulldozer!) and found evidence of Spanish Colonial campsites. The artifacts he uncovered convinced Wagner beyond a doubt that the shipwrecks lie just offshore, but how to go about salvaging them?

The Real Eight Company

Wagner was friends with some U.S. Air Force and NASA officers who were divers and “closet” treasure hunters, and in 1960 he partnered with them. Their first season of treasure hunting proved fruitless, but the group soldiered on.

Then, on January 8, 1961, everything changed. That day, Wagner and his group recovered more than 2,000 Spanish silver 8 reales, or “pieces of eight.” Within days, they established the Real Eight CompanyAlso referred to occasionally as “The Real 8 Company”- was incorporated in 1961. It had eight members….Kip Wagner, Kip Kelso, Dan Thompson, Harry Cannon, Lou Ullian, Del Long, Erv Taylor and Lis... More, aptly named because of its principal items of salvage and because there were eight partners. By Summer 1963, they were hot on the trail of a great treasure. In May 1963, a man named Bruce Ward found another gold-laden 1715 galleon just south of Fort Pierce, Florida (about 70 miles south of Sebastian Inlet).

As Wagner and his partners wrestled with how to leverage their limited resources so they might work both the Sebastian Inlet wreck and the new site, a young Californian, Mel Fisher, approached them. Fisher had his own financing and crew, so Wagner proposed that Fisher work the Fort Pierce site in partnership with Real Eight. In May 1964, Fisher hit the “Carpet of Gold,” a small area containing thousands of irregularly shaped Mexican, Peruvian and Colombian gold cobs (or macuquinos) — a 1715 fleet recovery unrivaled to this day. The National Geographic Society learned of the find and sent an agent to sign an exclusive, first-disclosure deal with Real Eight CompanyAlso referred to occasionally as “The Real 8 Company”- was incorporated in 1961. It had eight members….Kip Wagner, Kip Kelso, Dan Thompson, Harry Cannon, Lou Ullian, Del Long, Erv Taylor and Lis... More for the January 1965 issue of National Geographic magazine. Wagner accepted the offer, but he had a problem. Most of the partners wanted to sell some treasure immediately to recoup their investments.

They soon reached a compromise, conducting an auction in October 1964 that featured some great numismatic treasures, but they did not identify the items as 1715 Plate Fleet salvage. Dubbed the Ubilla-Echeverz Collection, the sale was a success nonetheless. (Three more auctions were held before Wagner’s death in 1972.)

The Florida Collection

In the 50 years since Real Eight’s first salvage efforts, work has continued in earnest on the 1715 fleet sites, sometimes with spectacular results. In July 1988, hundreds of high-quality Peruvian 8 escudos were recovered from Frederick Douglass Beach in Fort Pierce. But the most important development of the last half century is the State of Florida’s gradual accumulation of a world-class, public collection of Spanish Colonial coins and artifacts. Because fleet salvors must share 25 percent of their findings with the state, Florida has amassed a collection of more than 1,500 gold and in excess of 22,000 silver coins. (In 2000 Dr. Alan K. Craig published two important monographs on this subject: Spanish Colonial Silver Coins in the Florida Collection and Spanish Colonial Gold Coins in the Florida Collection.)

The Florida Collection categorizes its fleet coins by the four Spanish Colonial mints that were active when the treasure-laden ships set sail for Spain. Mexico City struck gold escudos and silver

reales for the viceroyalty of Nueva España (“New Spain”). Its small gold coinage (capped annually at a meager 158,440 pesos) was paired unevenly with an annual silver coinage that regularly exceeded 2 million and sometimes 4 million pesos. Ubilla’s galleons alone carried almost 5.25 million pesos in registered Mexican treasure. Not surprisingly, 77 percent of the escudos and 92 percent of the silver coins in the Florida Collection are Mexican cobs.

Santa Fe de Bogotá (in modern-day Colombia) struck gold escudos and a very small quantity of silver coinage. Thirteen percent of the escudos in the Florida Collection are from Santa Fe, while silver coins are represented by just five specimens!

In Bolivia (part of the viceroyalty of Peru), the mint at Potosí struck a substantial quantity of silver coinage (nearly 1.3 million pesos in 1715), while the mint at Lima, the capital of Peru, struck both gold and silver (about 1.2 million pesos in 1715). Ten percent of the escudos in the Florida Collection are from Lima, and 4 percent of the reales were struck at Potosí and Lima. Some silver reales from Spanish Peninsular mints and a few important gold escudos from an ephemeral mint at Cuzco in southeastern Peru complete the collection.

What follows are a few highlights of the four categories of 1715 Plate Fleet coinage. Ongoing research has yielded both important discoveries and some enduring mysteries.

Mexico City Mint. In late 1679, Mexico City, which had produced silver coins since 1535, began striking gold. Throughout the fleet era, the mint annually struck 1-, 2- and 4-real and 8-escudo coins, as well as half, 1-, 2-, 4- and 8-real denominations. All Mexican silver and gold coins, except for a few presentation pieces, were hand-struck on irregular planchets.

As noted, the disproportionate number of Mexican gold cobs in the Florida Collection, totaling 1,168 coins, was a bit of a surprise, as both Lima and Santa Fe produced more gold than Mexico during the fleet period, and because Echeverz’ flotilla was tasked to pick up whatever royal treasure from Peru was waiting in Panama.

The manifests excerpted by Farriss tell us that the 1715 Plate Fleet carried no royal treasure from Peru. Apparently, the viceroy of El Peru, remembering England’s attacks on the fleets of 1702 and 1708 during the War of the Spanish Succession, decided to send his gold and silver to Spain with a French convoy. As a result, Echeverz found only private shipments from Peru waiting in Panama and probably a small shipment of royal gold in Cartagena.

Prior to the fleet salvages, the entire Mexican gold coinage of 1679-1715 was represented by fewer than two dozen surviving specimens. Not surprisingly, Spanish numismatists were unaware that the cross design on Mexican escudos had changed five times between 1679 and 1713, and three times in 1714. Less than 1 percent of Mexican silver cobs show a legible date, so all fleet-era cobs clearly dated before 1714 (most of which were unknown prior to the salvage operations) are rare to very rare. Planchet shape varies widely, from round to rectangular or square, and every combination in between.

The mismatch of oddly shaped planchets and round dies guaranteed that much, if not most, of the designs did not transfer to the coins. The Spanish crown certainly did not like the appearance of its Mexican coinage, but other priorities delayed the money’s modernization until 17 years after the loss of the fleet.

The fleet salvages led to one very important discovery: a special series of large (36mm), round, multistruck Mexican gold 8 escudos dating from 1695 to 1715. Lima and Santa Fe de Bogotá did not strike similar coins. Craig calls these gold issues “galanos,” while in commerce they are referred to (since 1972) as “royals.” A second Carlos II royal exists: a 1695 onza that sold for nearly US $600,000 several years ago. A 1698 royal was produced from the same 1695 obverse die, with the “5” in the date carefully removed and replaced with an “8.”

This delicate re-dating confirms that the expensive royal dies were treated very gently and set aside for multiyear use (at least in the pre-1710 era). Although Spanish numismatists knew before the fleet era that single examples of this coinage existed for a few years after 1710, they had no idea why or how Mexico City was able to strike such beautiful coinage prior to mechanization in 1732. Ongoing research by several scholars is expected to explain the purpose for which royals were intended in Nueva España.

The Lima Mint. Throughout the fleet period, the Lima Mint struck both silver (beginning in 1684) and gold (beginning in 1696) in the same denominations as those produced in Mexico. Thanks to archival research conducted in the 1990s by Carlos Lazo Garcia and Guillermo Cespedes del Castillo, the actual Lima mintages are now known. Gold 8-escudo coins salvaged from the fleet are known for all dates from 1697 to 1714, with the exception of 1706. Apparently, no gold coinage was produced that year during a Peruvian gold rush!

Fleet salvages also have made Lima escudos from the reign of Carlos II collectable, though almost all dates and denominations remain rare. A possible exception is the somewhat more numerous 1699 gold coinage produced by Assayer “R” (believed to be Miguel de Rojas). From the beginning of the gold coinage in 1696, Captain Francisco Hurtado had been the assayer (“H”) at the Lima Mint and did a very competent job, based on the quality of the coinage. In 1699 he was replaced for one year by Assayer “R,” but returned in 1700, working another 11 years.

The sudden replacement of a presumably healthy assayer usually signaled an all-too-frequent secret investigation of his coinage. However, this theory is not supported by any documentation or by the evidence of the coins themselves. A second possible explanation is that Hurtado was temporarily assigned to other duties. A floundering branch mint, such as the one at Cuzco, would have been a suitable venue for Hurtado’s talents, though no known Cuzco coinage is associated with Assayer “H.” (His one-year “sabbatical” remains a priority topic for Lima cob researchers.)

Santa Fe de Bogotá Mint. Thanks to pioneering archival work by José Medina and A.M. Barriga Villalba, we know that the Santa Fe Mint opened in Bogotá in the mid-1620s, striking gold cobs annually and silver cobs intermittently until 1756. Prior to the fleet salvage, the 1689-1714 period was very poorly represented in the numismatic record, but now 2-escudo coins (plus a few 1-escudo specimens) are known for almost all those dates. The Florida Collection now has fleet-era 2 escudos dated 1689, 1699, 1700, 1701 and 1703-13.

The first surprise came when it became clear that the obverse legend on the 1701-14 escudos was CAROLUS II D.G. (On most escudos, only the first three letters are visible to the right of the shield.)

The unfortunate Carlos II died on November 1, 1700. Despite a disputed succession, Spain’s New World viceroyalties promptly declared for the Bourbon Philip, and by late 1701 or early 1702 they began to strike coinage in the name of PHILIPPUS V. The exception was the mint at Santa Fe. The Audiencia of Nuevo Reino supported Philip, but for 14 years, until the end of the War of the Spanish Succession, Santa Fe declined to strike coinage in his name.

In addition, an assayer’s mark is absent on almost all the coinage of 1701-14. Assayer Buenaventura de Arce evidently was as reluctant as the Audiencia to associate himself with the wartime coinage of Santa Fe. Why the Santa Fe Mint was allowed to strike an assayer-less, posthumous coinage for the first 14 years of Philip’s reign remains a mystery.

A second puzzle involves a Santa Fe 2 escudos that W. Frank Allen described in his 1967 article as the earliest gold coin from the fleet. While it is unquestionably a mint-state Santa Fe 1654 2 escudos, it is not the earliest gold coin attributable to the fleet, as a 1649 2 escudos in similar condition was said to be found with it. Following salvages (beginning in 1972) of the Bahamian wreck of the galleon Nuestra Senora de las Maravillas, lost in January 1655, high-grade 1654-dated 2 escudos are now the most common Santa Fe Mint gold coins available to collectors. (A few high-grade 1649 specimens also were recovered.) No Spanish coins salvaged from the Maravillas bear dates of 1656 to 1715.

The mint-state condition of these fleet coins belies the possibility that they lingered in circulation for 60 to 65 years before showing up on the 1715 fleet. (The next datable Santa Fe 2 escudos from the fleet is a 1689 issue.) Currently, there is no satisfactory explanation for the presence of mint-state 1649 and 1654 Maravillas coins at the 1715 fleet site.

The Cuzco Mint. Before the fleet salvages, the 1698 gold coinage of Cuzco (identified by mint mark “C” and Assayer “M”) was represented by just one or two examples. The only published piece was the Louis Eliasberg specimen that appeared in a 1935 Wayte Raymond sale. Medina and other scholars believed this coin was a pattern that was authorized, but never struck. However, when more than 50 Cuzco 2 escudos were covered from the fleet, all struck from five “pillar” obverse dies and three “cross” reverse dies, it became clear that Cuzco did indeed strike a substantial gold coinage. A handful of 1 escudos also was found. (The Florida Collection contains six Cuzco specimens).

The survival of so many, largely mint-state Cuzco coins on the 1715 Plate Fleet is a bit of a numismatic conundrum. By comparison, just two Lima 1698 2 escudos were found, and the total number of Carlos II 2 escudos (1696-1701) is 14. We could dismiss this as being a small, private hoard of 1698 Cuzco specimens traveling back to Spain in 1715, except that the coins show up at three sites associated with both the Ubilla and Echeverz fleets.

Archival work has shed no light on this puzzle or, for that matter, anything about the actual minting of coins at Cuzco. We do not know when the coinage began, when it ended, or how extensive it was. We cannot even verify the identity of Assayer “M,” although several texts confidently assert he was Felix Cristobal Melgarejo, the principal assayer at Lima in 1709 and 1711-27.

One striking feature of the fleet’s Cuzco coins is the inconsistency of their quality. From the same dies, the Cuzco coiners struck not only round, very attractive 25mm 2 escudos (the largest Spanish Colonial coins of this denomination), but also legendless, poorly centered 14mm specimens that are among the worst produced by any New World mint. The Cuzco facility obviously was experimenting with very different methods of planchet preparation.

Conclusion

Spanish Colonial numismatics clearly owes a great debt to the recovery of the 1715 Plate Fleet’s gold and silver treasure. New finds from the wreck sites cannot be discounted, especially in this era of deep-water salvage. Many of the questions already raised by the fleet coinage should spur numismatists to explore the rich, but neglected archives of Colonial Spain for answers.

SOURCES

- Allen, W. Frank. “Previously Unknown Spanish Coins.” The Numismatist (February 1967).

- Barriga Villalba, A.M. Historia de la Casa de Moneda. Bogotá: Banco de la Republic, 1969. (ANA Library Catalog No. FE55.B3)

- Cespedes del Castillo, Guillermo, and Gonzalo Anes Álvarez. Las Casas de Moneda en los Reinos de Indias, Vol. 1 (“Las Cecas Indianas en 1536-1825”). Madrid: Museo Casa de la Moneda, 1996.

- Christensen, Henry. The Ubilla-Echeverz Collection (October 8, 1964).

- Craig, Alan K. Spanish Colonial Gold Coins in the Florida Collection. Gainesville: University of Florida Press, 2000. (JD33.C73)

- Spanish Colonial Silver Coins in the FloridaCollection. Gainesville: University of Florida Press, 2000. (JD35.C73)

- Farriss, Nancy. “Translations from the Archivo General de Indias for the Real Eight Corporation.” Unpublished typescript, 1967.

- Flemming, Phil. “The Jeweled Cross Series of Mexican Gold Coinage, 1679-1699.” U.S. Mexican Numismatic Association (March 2013).

- “Varieties of the 1714 Mexico City 8 Escudos.” U.S. Mexican Numismatic Association (June 2014).

- Kamen, Henry. Philip V of Spain. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2001.

- Lazo Garcia, Carlos. Economia Colonial y Regimen Monetario Peru: Siglos XVI-XIX, Vols. I-III. Lima: Banco Central de Reserva del Perú, 1992.

- Medina, José. Las monedas coloniales hispano-americanas. Santiago, Chile: Imprenta Elzeviriana 1919. (FA15.M4)

- Lopez-Chaves y Sanchez, Leopoldo, with José Yriarte. Catalogo de la Onza Espanola. Madrid: Editorial Iber-Amer, 1961. (JD33.L6)

- Pradeau, Alberto F. Numismatic History of Mexico (with annotations and revisions by Clyde Hubbard). New York: Durst, 1978. (FB60.P7)

- Proctor, Jorge. Unpublished research on the 1715 fleet and early Mexican gold coinage. Personal communication, 2014.

- Raymond, Wayte, and J. Macallister. “J.C. Morgenthau Sale Number 345: The Waldo Newcomer Collection, Part I” (February 12-13, 1935).

- Wagner, Kip, with L.B. Taylor. Pieces of Eight. New York: Dutton, 1966. (CC55.W3)