by Ernie Richards

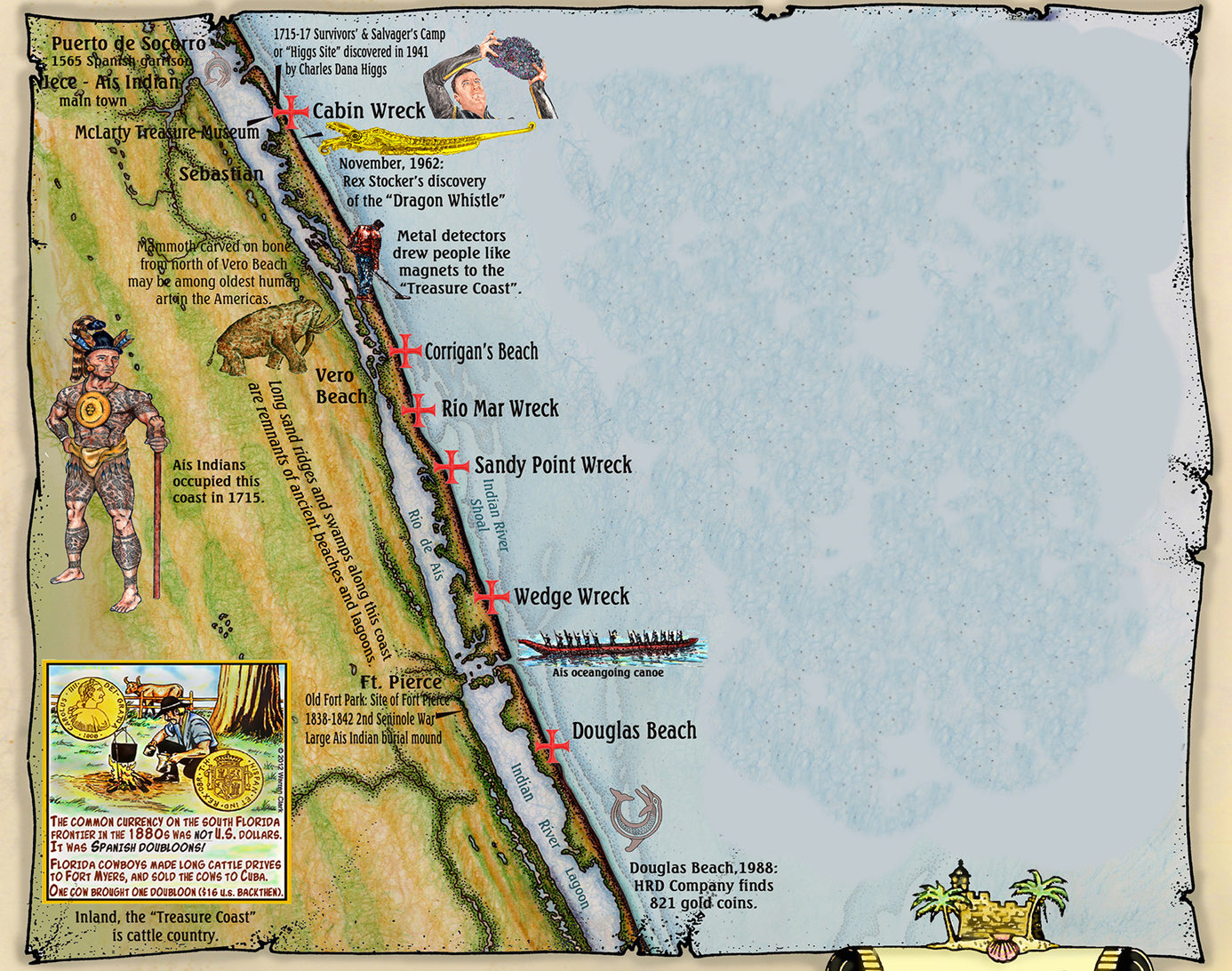

Just an hour’s drive north of here [WPB, FL] begins a 60-mile stretch of Atlantic waterfront that finds beachcombers making withdrawals from its sandy vaults nearly every day. From the St. Lucie Inlet to the inlet at Sebastian, lucky people swinging metal detectors —and others just kicking shells aside at the water’s edge— take home silver pieces-of-eight, gold doubloons, emeralds, and fabulous jewelry … all treasures from the Spanish Silver Fleet of 1715. Records of the day tell us that some 14,000,000 pesos of precious metals were registered aboard those eleven vessels which were destroyed by one sweep of Nature’s whimsical hand. The modern equivalency of a peso of that time (one piece-of-eight, for example) is somewhere between $100 and $200!

Yes, the returns are dwindling each year, but consider this: About one-third to one-half of this sunken booty was recovered contemporarily; another similar amount was gleaned from the wrecks by Spanish salvagers and English raiders from the Bahamas in the five or six years that followed. This left a large fortune for the divers and shell-kickers of today. The hunt has been underway for over fifty years, and each year the finds make headline news. In the 1960s, divers were recovering silver coins, literally, “by the tons”! By my count, more than 10,000 gold coins have once again seen the light of day since this craziness began in the late 1950s with a man named Kip finding a single one-ounce gold coin in a receding wave at a remote strand of sand in Wabasso.

The following is a nutshell history of this phenomenal connection through time, from yesteryear to as recent as last week. It is adapted from a short story I wrote called Treasure Treachery! —ER

In late July, 1715, the combined treasure fleets of Captain-General Don Antonio de Echeverz and Captain-General Juan Esteban de Ubilla —eleven strong— plus a French merchant ship in custody left the harbor at Havana on their way back home to Europe. They never got past Cape Canaveral.

Bulging with some 14 million pesos in gold and silver, the armada was caught in the narrow waist of the Bahama Channel by a ferocious Atlantic hurricane and was demolished along the east coast of Florida from St. Lucie Inlet to Sebastian Inlet. Only the French ship survived to sail another day. The toll in human life amounted to nearly 900 souls, the exact amount still hidden in the records of the day.

Survivors on this desolate and forbidding shore began to reassemble their lives the very next day, retrieving and burying those who washed up on the beaches, seeking fresh water, and establishing makeshift shelter from ship’s flotsam. Dispatching messages to the Spanish settlements at St. Augustine and Havana, the survivors then began the necessary task of salvaging cargo and treasure from the vessels which had burst their hulls and spilled their goods on the nearshore reefs. Within weeks, the survivors were rescued and carried to Spanish ports to await transportation back to Spain.

The salvage camps remained busy for the next three or four years, the Spanish reclaiming precious cargo from the ocean when weather and sea state permitted. English pirates boldly raided the Spanish camps from the safety of their ports in the Bahamas, helping themselves to the doubloons, pieces-of-eight—and more—that King Philip’s subjects had laboriously extricated from the submerged rocks and sand. The enterprising pirates returned after the Spaniards gave up, and they “fished” over the wrecks for a few more years before the tragedy became a distant memory and a footnote to colonial history.

Then, in the late 1950s and early 1960s, a local man, Kip WagnerKip Wagner (1906 – 1972) was instrumental in the formation of the team that later became the Real Eight Company and one of the greatest salvage groups that ever explored the 1715 Fleet wrecks. He ... More, began finding Spanish silver and gold on the beaches here and realized that there must be an old ship lying on the reefs just off shore. Research in Spain revealed that not just one ship, but ten or more galleons and merchant ships of a large treasure fleet, had been lost along a sixty-mile stretch of this coast.

Wagner formed a corporation, Real Eight, and began the search and recovery operations which blossomed into an industry, its magnitude approaching that of the Gold Rush of 1849 in California. So much gold and silver was recovered from the remains of these ancient ships beginning in the 1960s that this part of Florida’s seaboard was soon dubbed the “Treasure Coast,” a moniker which has permanently attached itself to the area and area businesses.

Mel Fisher successfully fished for treasure here before moving his operation to the Keys. Bob Marx spent some productive time on these wrecks. More recently, Mo Molinar and John Brandon (formerly part of Fisher’s teams), Bob Weller, and others have kept up the Treasure Coast tradition by making headline news with their recoveries. And the beat goes on…!

Living in the shadow of that great fleet, many a local beachcomber with a metal detector has pocketed gold and silver coins and beautiful jewelry found on these rugged strands of Atlantic shoreline. And from around the world come the curious and the adventurous, some carrying detectors, some kicking seashells aside to see what else might be lying there, but all hoping to experience the “thrill of the find.”

When the quest for that “thrill” becomes an obsession, all reason can go out the window, and one can come down with “gold fever!” This affliction can affect even an otherwise healthy person, transforming him into someone “driven” by greed or lust for instant wealth, someone who will even “step over the legal line” and deceive or steal, losing friends and family in the process. A good sign that somebody has caught this virus: When he sees or holds a piece of treasure, his pupils narrow, his eyes glaze over, and his attention span disappears … as does his power of reason. We have seen it!

Go ahead! Get “the fever”! You may get filthy by digging in the sand, but you will not get filthy rich. Besides … 90% of the thrill is in the hunt! Take it from me…

GOOD HUNTING!

Ernie Richards